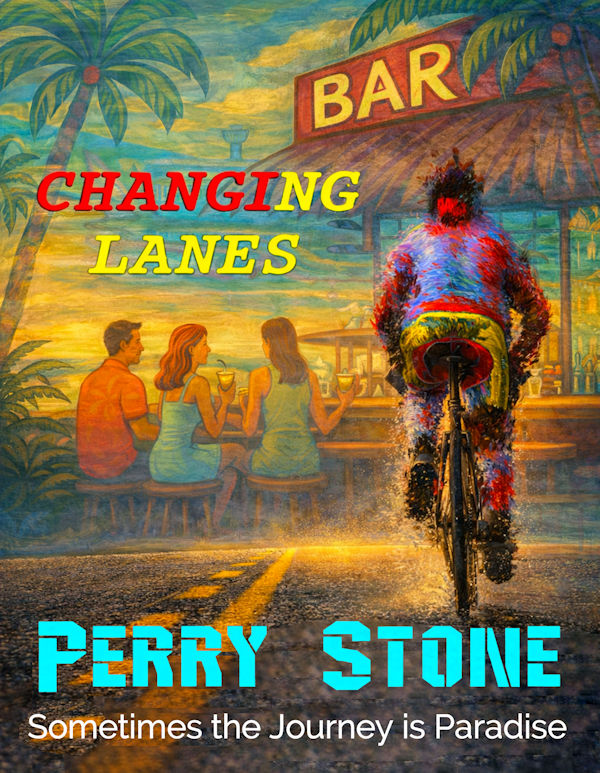

Changing Lanes is a sneak peek inside a writer’s workbook.

As an ultra-endurance cyclist, I once read Ernest Hemingway’s last book, True at First Light, while riding my bicycle across the Australian Outback. Not when I was resting, but when I was pedaling.

In the book, Hemingway was a game warden. His five-foot-nothing-tall wife was a lion hunter. Back then, there was honor and a life-and-death art form in being a big game hunter — a chess game in which you studied the lion for maybe months to learn its habits so that one day you could stand before it with your rifle and determine, with finality, who was the king of the jungle. If you were going to hunt a lion, it had to be a duel where the lion had a fair chance at killing the hunter.

They would lie in their tent at night under their mosquito nets and listen to her lion roar at the moon — a sound that fascinated them both, knowing that one day soon, with the sun rising over the Serengeti, the lion or the hunter would die.

I would read both sides of a page, then tear it from the book and release it into the Outback. I never considered it littering; it was more like spreading beautiful magic over the limestone.

I always dreamed I could write while riding, but I had to just daydream stories and try to remember them sufficiently to write them all down when I was stationary.

Changing Lanes is the result — a somewhat eclectic collection of stories about my masochistic pursuit of distance behind the bars of a bicycle and the tales I read in the wind, sights, sun, and motion.

There is some very adult behavior in this collection, but it is more like seasoning than the main course. After you read these “departures from normality,” you will never think of the lone cyclist encountered in the middle of nowhere in the same way ever again.

True at First Light inspired me, and I am paying it forward with Changing Lanes, hoping it just might inspire you to check in with your wild side.

I was limited to the ghosts of lions, as every piece of tumbleweed I glimpsed moving transformed into a lion in my mind. It was a profoundly primal exposure to survival and the mysticism of our natural world. On the Nullarbor Plains, under a hundred million stars, I met a witch and dined on roadkill with her.

There are some things you cannot understand, but you are still meant to digest.

Bon appétit.

Excerpt One

Then nothing… just a heartbeat: the exerted breath of the rider, the whir of chain and gears meshing, the wind in his ears as he cuts his way through space and distance, as almost everything else becomes all but silent in the desert. His breath and the manifestations of the bike are like lovers breathing in unison after the celebration of ecstasy. A surreal moment that seduces and encourages the timid night creatures; emboldened by the silence, the cricket’s song resumes center stage ever so briefly before a monster’s presence can be heard. The distant rumbling roars of a road train quickly serve to remind the rider that he is not the only human night creature on this path. The noise becomes lost in the shifting, dancing winds, and a muffled sort of silence erupts again. Everything combines in a nocturnal overture that delivers a profound understanding of the rider’s place in the universe.

Then nothing… just a heartbeat: the exerted breath of the rider, the whir of chain and gears meshing, the wind in his ears as he cuts his way through space and distance, as almost everything else becomes all but silent in the desert. His breath and the manifestations of the bike are like lovers breathing in unison after the celebration of ecstasy. A surreal moment that seduces and encourages the timid night creatures; emboldened by the silence, the cricket’s song resumes center stage ever so briefly before a monster’s presence can be heard. The distant rumbling roars of a road train quickly serve to remind the rider that he is not the only human night creature on this path. The noise becomes lost in the shifting, dancing winds, and a muffled sort of silence erupts again. Everything combines in a nocturnal overture that delivers a profound understanding of the rider’s place in the universe.

On the other side of gravity, millions of years away, distant planets and nebulae flicker and shine. What brought us the wisdom and hope of mythology now hints at the secrets of life itself. Stars a billion lifetimes old suddenly sacrifice their mysterious origins in furious disarrays of brilliant white-blue, momentarily etching their glory in his eyes. Slightly beneath the heavens, satellites streak like rockets as if to say that man will not be outdone — but the rider just rides. His pedals crank in unison with the rotation of the earth.

Excerpt Two

Suddenly, we banked and dropped out of the sky about 1,000 feet, leaving about 2,000 feet until Mother Earth. I noticed one fuel tank was empty, and the other was indicating that half its reserve was gone. Then, finally, I saw Darwin International Airport. We had to cross over the Timor to get to it, and I was convinced it was here that we were going to land — not at the airport.

Suddenly, we banked and dropped out of the sky about 1,000 feet, leaving about 2,000 feet until Mother Earth. I noticed one fuel tank was empty, and the other was indicating that half its reserve was gone. Then, finally, I saw Darwin International Airport. We had to cross over the Timor to get to it, and I was convinced it was here that we were going to land — not at the airport.

As we made our bumpy progress, things on the ground grew more recognizable. I could make out the lay of the city, and it looked like we might make it now, or if we didn’t, we would at least be reasonably close to emergency services.

Then, in a move completely unexpected by either Libby or me, the boy pilot — in all his infinite wisdom — put the plane into a hard banking turn away from the airport, heading us out over endless mangroves. It was possibly the only place worse than the sea for a crash site. Mud — total inaccessibility by emergency response vehicles — was everywhere. The crocs slithered every which way on the muck below.

I thought I might have to knock Libby out, as she was obviously on the very thin edge of losing it now. None of us, including her, needed that.

I asked the boy pilot the reasoning for his flight reversal: “What? You forgot your sunnies back on the beach?”

“The crosswinds are too strong. The tower sent me away. We have to try to wait it out. There is nowhere to go with our fuel supply. At some point, if it comes to it, we attempt a landing before we run out. The problem is, the gauge flickers all over the fucking dial. The best I can do is keep positioned to go in at first sputter. The sputter is our advanced warning system.”

I guzzled the Jack Daniels, then jammed it down Libby’s throat; she drank it like a compulsive glutton.

Now the engine was our complete and utter lifeline. All three of us hung on to every beat in its rhythm. Milkboy twisted his head, a little too Exorcist-like, and screamed, “Look under your seats! Quick, look under your seats — there should be two parachutes!”